Tales from a Paranormal Childhood: I think there’s a Pooka in the Living Room

I have always loved the man-made sounds that break the quiet of the night: passing cars, train whistles, the morning newspaper being delivered. These sounds, particularly in my youth, offered me comfort and safety, someone else was awake, alert, standing guard without any knowledge of their appointment to this powerful and protective role. My fear of the night was well-known in my family and lasted inappropriately long–well into my late teens–dissipating only when I entered college and moved into a dormitory that housed more than 500 wonderfully nocturnal humans. But before this Heaven-on-Earth housing assignment, deviations from my nighttime routine were rare: Fan, check. AM radio set to the staticky overnight talk shows that were broadcast from Cleveland, check. Corner lamp on, check. TV off, check. That last requirement may seem counter-intuitive but it was the 1970s, and to be awakened by the National Anthem and subsequent sign-off tone at the witching hour of 2:00 AM was the kiss of death for me. The parameters of acceptable waking times were rigid- to be awakened before midnight or after 4:00 AM were safe; after all, my dad got up for work at 4:30 and then dawn was close enough to allow me to slip back into my slumber. If, God forbid, I opened my eyes in that 4 hour window of terror, my fate was sealed: I would lay motionless, paralyzed, sweating from a combination of fear and now-suffocating blankets that I refused to come out from under, listening for unexplainable noises, and waiting for some unknown force to find me. I wanted to cry, but my silence hid my presence while I prayed for dawn to come. What was I expecting might happen? Who or what was I waiting for and hiding from? Many years would pass before I understood the cause.

My sister, Heather, was my loyal companion throughout much of my introverted childhood existence. She was two years my junior and always included me in with her circle of friends. Her devotion extended into my nightly wee-hours requests for accompaniment to the bathroom, and it rarely took more than a light tap to get her to rise, without speaking, to join me on the trek down the 1970s avocado shag-carpeted hallway. On one particular night, timestamped only by the matching nightgowns recently sewn by our mother (Simplicity circa 1976), our nightly journey would quietly but profoundly transform the rest of my childhood.

To set the stage, picture a split-level middle class Midwestern house that sat as the neighborhood anchor where all the tar-covered streets converged. We were the only house with a swimming pool in the yard, albeit an above the ground find from the local salvage store, but it was the summer yard where neighborhood bikes would lay as plans were organized for the day among the young riders, and neighborhood ladies would gather for some sun, cigarettes, and chatter. Inside, shades of orange and green dominated, with a velvet sofa and chairs in the living room, and a brown and yellow plaid couch that paired well with the fashionably-paneled walls in the den. All floors carpeted and all walls papered in florals, trellises or bicentennial charm. A black wrought-iron rail led up the stairs and wrapped around to a balcony landing on the second floor, with a spectacular mirror-tiled wall for the backslash. It was this mirror that reflected the image of my sister and I in matching nightgowns, ages 6 and 8, as we walked from our shared bedroom side-by-side that night.

The first hint of oddity came from the flood of light that blinded our night eyes as we made our way to the bathroom in those still pitch-dark hours. The living room glowed. Every light was not only on but also seemed much brighter than usual. A child’s mind rationalizes quickly, and I dismissed the strange illumination as the result of forgetful parents. As Heather and I got closer to the wrought iron railing that separated the elevated hallway from the living room, I saw something moving… walking actually… from the living room toward kitchen. In sync, Heather and I kneeled down in front of the railing, our hands holding the cold metal rails while our faces peered through to see the creature that stood down below. It was a very large white rabbit, standing upright. It stood at least 7 feet tall and if I had stretched my hand out through the rails, I could have touched it. It stopped instantly when it became aware of our presence and turned its head quickly to meet our now-frozen faces. The massive creature had a colorful poncho of some kind over one shoulder and a sack over the other, amusing enough that I don’t remember feeling frightened; what I do remember were the rabbit’s large eyes–almond-shaped and onyx black, like the darkest waters of the ocean at its deepest point. The eyes were the whole of the creature, not the costume it had wrapped itself into. It communicated with us and the message was clear, “Get up. Go back to bed. Never speak of this night again.” I heard the message from somewhere in my head, but not through my ears. No sound was ever made and the rabbit’s mouth never moved, but I knew Heather had received the message too, because we stood up together and followed the clear instructions we had been given.

It must have been something about the safety of that dorm, the distance now placed between my childhood home and this college town, that allowed the memory of that night to catapult from its hiding place and into my conscious mind some 10 years later. It was there suddenly and completely, and I shared it with my roommates–one of whom was an art major–and soon she had sketched, almost perfectly, the creature she named “Demon Bunny.” It was a vividly detailed memory without question, and my roommates and I brainstormed the rational and the irrational possibilities: a dream? a nightmare? an alien? a burglar? The weekend following my revelation, I headed home for a visit that included a shopping trip with my mom and sister. Demon Bunny was now alive and well in my mind but its message was still firmly fixed–”Never speak of this night again”–and I was fearful of the consequence that might follow if I violated that pact.

I had decided to share my story with my mom and Heather, and I finally threw caution to the wind as we drove along on our shopping trip, “You know, I had the strangest memory come back to me recently. I think it was a dream… haha… but here it goes…” I told my story to my mom and sister, both with very different reactions. My mom’s concerned and confused stares alternated back and forth from the road to her narrating passenger and back again. Heather, who had been relaxing in the back seat now slid her body forward and leaned her whole head into the front seat space between my mom and I, her face drained of color. “That wasn’t a dream. I remembered it a few years ago, ” she said. My mom nearly drove off the road, asking why she hadn’t talked about it before this moment. I already knew the answer. My sister, just inches from my head, and with a now deeply accusatory and worried tone directed her response at me, “Because we were told not to.” With the cat, or more accurately the rabbit, out of the bag we compared stories, matching detail to detail the events of that night–the lights, the colored poncho, the sack, the eyes, and the message. My mom, who had just finished the alien-based book Communion: A True Story, was convinced that the rabbit was an extraterrestrial. My sister committed to silence on the topic after that weekend and today remains hesitant to discuss it any further. I have done some research into the topic over the years and while I felt ridiculous entering the search words “big white rabbit in my house”, “rabbit with eyes that spoke to me”, and “do shape-shifters exist?” into my computer, I did stumble across a concept from Celtic folklore that seemed to check many of the boxes: the Pooka.

The word “Pooka” is believed to have come from the old Irish word for Goblin (puca) or perhaps the Scandanvian word “pook/puke” meaning ‘nature spirit’. According to the lore, it appears only at night, enjoys creating mischief, and it is often inclined to conversation. They can take the form of any animal, although most commonly they appear as horses with glowing eyes. Pookas are credited with being benevolent, protective, and sometime havoc-wreakers. They often leave those who encounter them with a questioning of whether or not the visit was even real. One of the first things I ever read about Pookas was that when they appear to a child, they seek to forever alter the perception of reality for that child. Hollywood has borrowed the Pooka for now-famous films like Harvey (1950), Donnie Darko (2001), and Pooka (2018). I’m still not sure what we saw that night, but I don’t think was a “demon” and I certainly hope it wasn’t an alien. I can live with the idea of the Pooka so that’s where I landed. I’m fascinated to hear other people’s stories of unexplained events that may be similar to mine. What happened and how did it affect you?

Life Lesson #1: What I learned about vaccines from my dead relatives.

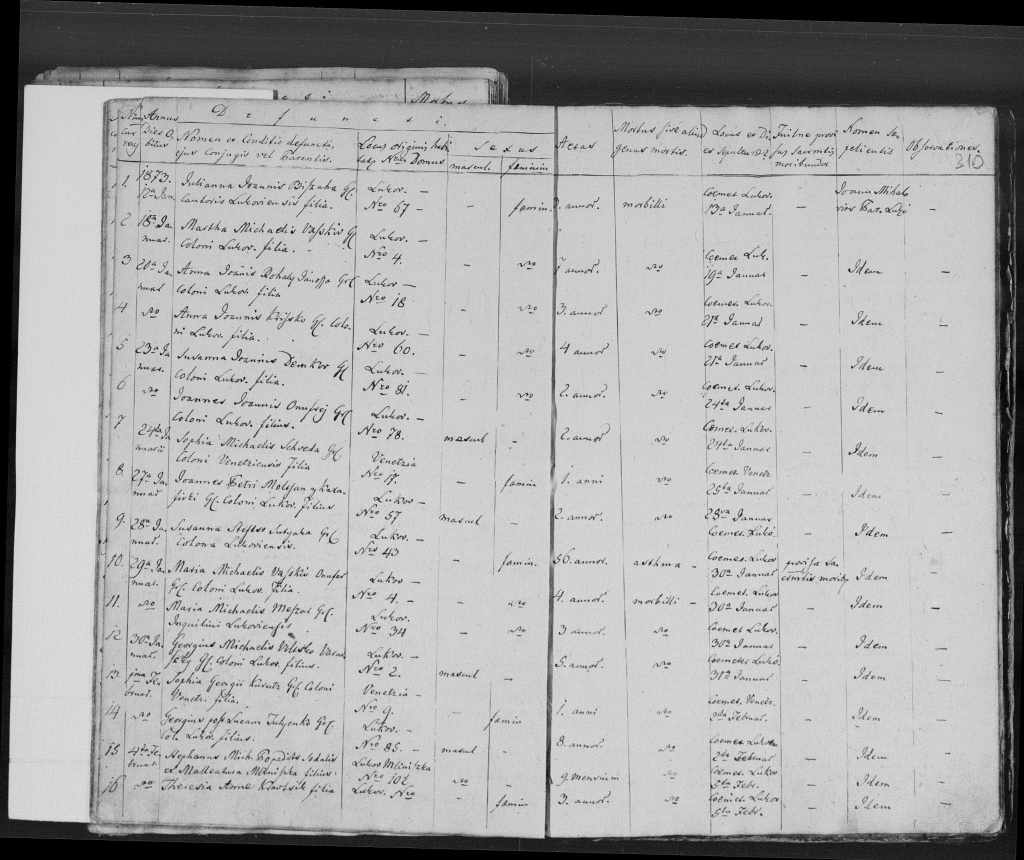

Anna Mikita was murdered by her second husband in the small Slovakian village of Lukov-Venecia some time after 1889 and before 1906. The life insurance policy taken out by her son, John (Joannes), in Cleveland during the 1920s told the tale: Father, “deceased in old country 1887” and Mother, Anna Mikita, “killed by husband” (length of “illness” inflicted at the hands of this second husband was noted as “3 days” but without a date of death). For a genealogy researcher, this was gold, but for the great great granddaughter of Anna Mikita, not so much. Poor Anna Mikita. I dove into the detailed church records of the village searching for answers.

“Diving in” implies a smooth and rapid entry into the clear waters of organized and detailed logs of the births, baptisms, marriages and deaths of my Slovak ancestors; what I did was more of a belly-flop into records written in Greek, German, Latin, Hungarian and Russian and into a Carpatho-Rusyn village of Greek Catholic tradition that involved a very small database of boy and girl names: Joseph, Michael, Joannes, Georgius, Petrus and Julianna, Anna, Maria, Paulina, Susanna. Dwellings by house number helped me sort families, and on a large white poster board I drew the village–placing my relatives immediate and distant in their respective houses. I went back to the year 1800 and moved forward, gathering a sense of community and belonging as I peered through that small window into the past- how nice, Julianna and Michael in House #6 had a baby boy! (Also named Michael, which would be less confusing had it not also been the name of the infant boy they lost to febris nervosa- which didn’t sound good- 15 months earlier.) Hours, days, and weeks passed. I taught myself enough Latin to read through the sacred, scripted books online that trailed off my screen and drifted the now-living dead into their crudely drawn squares on my treasured poster board village.

Anna Mikita was born in Lukov-Venecia in 1857 and married Joannes Kuritz in 1878. Joannes was 60 years old at that time, and Anna was his second wife. His first wife, Maria Rohaly, had died of typhus in 1877 along with their 6 year old son, Joannes, in House #12. But wait- there was another young Joannes born in House #12 in 1868 who was now uncounted for… it couldn’t be an error in dates or records because they were meticulously detailed. I had missed the death of the first son, remembering that they simply recycled the names of deceased children according to birth order. I would have to go back to 1868 and pay closer attention to the deaths in the village, the “Morbus sive aliud genus mortis” aka “Illness or Cause of Death.”

“Morbilli.” I thought it meant general death, maybe of an unknown cause, and it killed a lot of children. Between January and March of 1863, 27 children in the village died starting with 2 year old Maria in House # 55 and ending with Susanna, 5 months old, in House #47. A second major wave of “morbilli” hit the village in January 1873 and resulted in the deaths of 37 children. Some quick Google searches later and I had accessed a page of Latin causes of death. Morbilli was measles. In April of that same year, “variola” (smallpox) arrived, killing 4 more children. Adults weren’t spared in 1873- Cholera killed 34 people in Lukov-Venecia between July and September. These weren’t the only deaths that year in the village: diphtheria, thyphus, asthma and colic also took many lives. My ancestors must have been as glad to see the end of 1873 as I was to see the end of 2020. In the midst, I discovered that the first Joannes born to Joannes and Maria Rohaly had died at 6 months old of colic.

I always wondered, long before Covid, what the impact might be if these old church records were used in a public campaign encouraging people to vaccinate their children. Simple posters with photocopies of what it looked like, in factual black and white, when a measles, diphtheria, or pertussis outbreak hit a village in Europe in the 1800s; the physical pain of the disease without relief, the suffering of the children and their families, the devastating grief that would follow the death. Although the potential for childhood death was expected (it took 3 times for my great grandfather’s name of Joannes Kuritz to survive into adulthood), I doubt it was accepted any more than losing a child is today. I wonder what Anna Mikita, Maria Rohaly and Joannes Kurtiz would say if they knew that today we have a simple vaccine for these illnesses that took away their siblings, cousins and children- but that some people refuse to use them. I wonder what the ancestors of anti-vacciners would say, or how they might beg or implore their descendants to rethink their decisions. I think that most of those decisions are made from a place of fear, but I also think there must have been nothing more terrifying for these powerless villagers than the news that measles, smallpox, diphtheria or pertussis were once again spreading through their streets.

The years of research I have done as the self-title “Family Genealogist” have taught me endless life lessons. I have followed my ancestors as they immigrated from modern day Slovakia, Ireland, and Scotland to the Midwest of the United States. Countless men in my family fought in the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, WWI and WWII. My great grandmother traveled from Scotland to Indiana in 1902 with five children under the age of six to meet up with my great grandfather, who had immigrated the year prior to secure work in the coal mines. My paternal grandmother’s letters to her two brothers serving in WWII shed light on a dark and difficult period of history, from polio and quarantine, to food rations, to overwhelming worry and fear. Ultimately, Anna Mikita’s death record was lost during the conversion of church files into the state archives, so her fate remains a search for another day. In the end, I carry these stories with me and when faced with adversity, I often remind myself that if my ancestors could survive life’s challenges, so can I. I cannot understate the amount of pride I have in every one of them, I hope they are proud of me, and I wish to be remembered proudly. There is a tiny blip on a timeline that we get placed on at birth and that timeline continues long after the tiny blip of our death. The goal of humanity, minimally, should be to keep that timeline going with the least amount of pain and suffering as is possible for future timeline riders. We can’t change the past, but if we can make the ride smoother, happier, or less filled with strife for our descendants, isn’t it our obligation to do so?